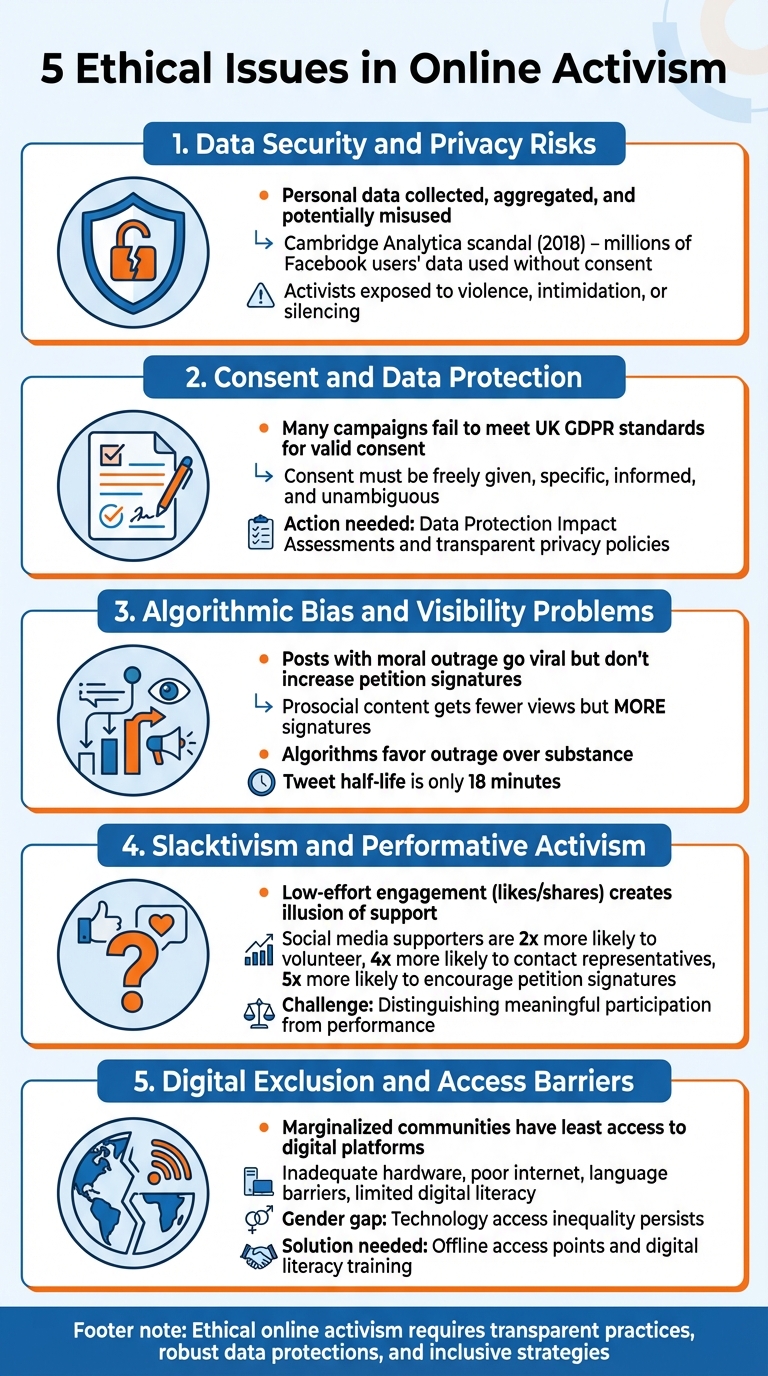

Online activism has reshaped how social movements operate, but it comes with ethical challenges. Activists face risks like data misuse, biased algorithms, performative action, and unequal access to digital tools. These issues can undermine the effectiveness and fairness of digital advocacy. Here's a quick overview of the five key challenges:

- Data Security and Privacy: Activists' personal information is often collected, shared, or misused without proper safeguards.

- Consent Violations: Many campaigns fail to meet proper standards for obtaining clear and informed consent.

- Algorithmic Bias: Social media platforms amplify outrage-driven content, often sidelining meaningful campaigns.

- Performative Activism: Shallow gestures like "likes" or shares can dilute genuine efforts for change.

- Digital Exclusion: Marginalised groups often lack access to the digital tools needed to participate.

To address these challenges, activists need transparent practices, robust data protections, and strategies to bridge the digital divide. Ethical online activism requires more than just raising awareness - it demands responsible and inclusive approaches.

5 Ethical Issues in Online Activism: Key Challenges and Solutions

Social media is getting worse, but it is useful to activists (ft. @UnmoderatedInsights )

1. Data Security and Privacy Risks

Engaging in online activism - whether signing petitions, joining campaigns, or interacting with advocacy groups on social media - often involves sharing personal details like names, email addresses, locations, and even browsing habits. Companies like Meta and ByteDance collect and retain this data, which can then be aggregated, sold, or misused in other ways.

A particularly concerning practice is microtargeting, where data analytics are used to deliver highly tailored political messages, often without users' explicit consent. By combining activist data with publicly available information through techniques like web scraping, campaigns can obscure how this data is being used.

The 2018 Cambridge Analytica scandal serves as a stark reminder of the dangers. This consulting firm acquired data on millions of Facebook users without their consent and sold it for political purposes, including Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign. The scandal exposed the alarming potential for data misuse within online political advocacy.

But the risks go beyond corporate exploitation. Data breaches can have severe real-world consequences for activists, exposing them to threats like violence, intimidation, or attempts to silence them. The rise of the surveillance economy, coupled with unchecked data collection, underscores the urgent need for robust data privacy measures - especially for those involved in dissent or advocacy.

To protect themselves, activists should carefully review privacy policies, only give consent when fully informed, and reject data use for direct marketing purposes. Building digital literacy and practising online safety are essential steps to minimise these risks. In the next section, we’ll delve into how consent challenges further complicate data protection in online activism.

2. Consent and Data Protection

Collecting personal data without proper consent isn't just a bad practice - it’s a direct violation of UK GDPR. Yet, many online campaigns still fall short of meeting the high standards required for valid consent, leading to serious ethical and legal concerns.

UK GDPR Article 4 defines consent as a freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous agreement by the individual. This means activists cannot bury data collection details in long-winded terms or rely on pre-ticked boxes. Instead, people must actively agree - whether by ticking a box or signing - to allow their data to be used.

For campaigns using cookies or tracking pixels to target political messages on social media, prior consent is mandatory under PECR Regulation 6. Activists cannot fall back on excuses like "legitimate interests" as a justification.

The stakes are even higher when it comes to processing sensitive data, such as political opinions. If a campaign gathers or deduces information about someone’s political beliefs, explicit consent is required. This rule applies whether the campaign is running its own petition or using third-party platforms. Additionally, when social media platforms are involved in targeting, both the campaign and the platform may be considered joint controllers. In such cases, formal agreements clarifying each party's responsibilities are crucial.

Transparency is non-negotiable. Activists must inform individuals upfront about what personal data is being collected, how it will be used, and who it will be shared with. For instance, if email addresses are used to match individuals on social media for political messaging, this must be disclosed before data collection - not buried in a privacy policy. Similarly, if data like petition signatures will be reused for future campaign targeting, fresh consent must be obtained.

Many campaigns face challenges meeting these requirements, particularly when combining data from various sources, including web scraping. This type of "invisible processing" - done without the user’s knowledge - carries significant risks. To steer clear of such issues, activists should:

- Conduct Data Protection Impact Assessments before launching campaigns.

- Ensure consent requests are clear and separate from other terms.

- Honour objections immediately. For example, if someone opts out of direct marketing, their data cannot be used for targeting or creating "lookalike" audiences.

Next, we’ll delve into how algorithmic bias adds another layer of complexity to digital activism.

3. Algorithmic Bias and Visibility Problems

Social media algorithms play a major role in deciding which activism campaigns gain traction and which fade into obscurity. These systems are programmed to prioritise content that stirs strong emotions and moral outrage, creating a disconnect between what spreads widely and what truly drives action. This raises important concerns about the actual effectiveness of online activism.

Recent research sheds light on this issue. A study published in Social Psychological and Personality Science in April 2025 highlighted a striking contrast. Posts expressing moral outrage were far more likely to go viral on platforms like X (formerly Twitter), yet they didn’t result in increased petition signatures. On the other hand, posts focusing on helping others - known as prosocial content - were less likely to gain viral attention but led to a much higher number of signatures. Dr Stefan Leach from Lancaster University summed it up:

"The most significant result is a double-dissociation. We find that expressions of moral outrage are directly linked to the virality of online petitions but not to the number of signatures they receive. Other expressions, such as those about helping others (i.e., prosociality), had no link to virality, but did predict a greater number of signatures."

This highlights a troubling reality: algorithms favour outrage over substance, often sidelining campaigns that could inspire meaningful action. The problem is worsened by the rapid turnover of content on social media - a tweet’s half-life is just 18 minutes. In such an environment, thoughtful, impactful campaigns struggle to compete with the emotionally charged content that algorithms boost.

Adding to the complexity is the lack of transparency in how these algorithms work. Platforms rely on a mix of user-provided data, observed behaviour, and inferred patterns to microtarget political messages. This leaves activists in the dark about why their campaigns reach some audiences but not others. A stark example of this power imbalance came to light in 2014, when Facebook manipulated users’ news feeds to influence their emotions, revealing the extent to which platforms control content visibility. Even well-meaning activism can backfire - during #BlackOutTuesday on 2 June 2020, millions of users posted black squares with the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag, unintentionally burying critical information about the movement.

Understanding these biases in visibility is essential as we navigate the ethical challenges of digital advocacy. Without addressing these issues, the potential for meaningful activism to thrive online remains limited.

sbb-itb-24fa5d9

4. Slacktivism and Performative Activism

Online activism, while powerful, struggles with the quality of engagement it fosters. The convenience of digital platforms has led to a trend where users "like" or share posts with little thought or commitment. This practice, often referred to as slacktivism, involves minimal effort and rarely results in meaningful change. It creates the illusion of support but can dilute the impact of genuine advocacy.

Slacktivism often prioritises individual validation over collective progress. Some participants focus more on self-promotion than on advancing a cause, which weakens alliances and fragments movements. For instance, during the Black Lives Matter movement on TikTok in 2022, white influencers frequently overshadowed the voices of racialised communities directly affected by police brutality. Similarly, when actress Alyssa Milano amplified the #MeToo hashtag on Twitter in 2022, the campaign's viral success unintentionally sidelined black women and women of colour, whose experiences were central to the movement’s origins.

However, it’s not all negative. A study by Georgetown University revealed that people who support causes on social media are significantly more active in both online and offline advocacy compared to those who don’t. These supporters are twice as likely to volunteer, over four times as likely to contact political representatives, and five times as likely to encourage others to sign petitions. This highlights the importance of distinguishing between superficial gestures and actions that create real-world change.

The ethical challenge lies in recognising when online activism shifts from meaningful participation to mere performance. When shallow actions replace collective effort, the potential for activism to drive meaningful social change diminishes.

5. Digital Exclusion and Access Barriers

The digital divide presents a major ethical challenge for online activism: the people most affected by injustice often have the least access to digital platforms. Research from the University of Sussex highlights this disparity:

"Evidence tells us that people with greater capital (economic, social, and cultural) have better and more effective access to social media".

This means that marginalised communities - the very groups that activism seeks to uplift - are often left out. They may lack access to devices, reliable internet, or the digital skills needed to participate fully in online movements.

These barriers are widespread and multifaceted. Many individuals face challenges such as inadequate hardware, poor internet connectivity, language barriers, and limited digital literacy. The University of Sussex further points out:

"while social media has given a platform to many people rarely heard from in mainstream media, there is still a large demographic globally that these platforms don't serve".

Gender inequality adds another layer to this issue. Brooke Foucault Welles, Associate Professor at Northeastern University, and Meighan Stone, former Adjunct Senior Fellow at the Council of Foreign Relations, emphasise:

"the gender gap in technology access remains persistent".

These digital access barriers carry serious ethical implications for inclusivity. Campaigns that rely solely on digital platforms risk excluding key voices, weakening their impact and legitimacy. When activism operates exclusively online, it inadvertently silences those who lack digital access, leaving out critical perspectives. Duncan Green of Oxfam cautions:

"Exclusion: some groups are better connected, or more comfortable with social media, than others. They will come to dominate".

This imbalance undermines the democratic potential of online advocacy.

Addressing the digital divide requires tangible solutions. Activists need to provide offline access points, offer digital literacy training, and ensure that information reaches communities through non-digital methods. The message is clear: activism has a responsibility to include everyone, not just those with digital access.

Conclusion

Online activism brings with it five key ethical challenges: data security, which exposes activists to risks like surveillance and harm; consent and data protection, where personal information is often collected without proper safeguards; algorithmic bias, which can silence marginalised voices by influencing visibility; slacktivism, which reduces meaningful engagement to superficial gestures; and digital exclusion, which risks leaving behind the very communities that activism aims to support, undermining its inclusivity.

To ensure online movements remain inclusive and responsible, ethical practices must take centre stage. This involves taking clear steps such as obtaining explicit consent before collecting personal data, implementing transparent and accessible privacy policies, and conducting thorough Data Protection Impact Assessments when dealing with high-risk data processing. Addressing algorithmic bias is also crucial to ensure fair representation, while integrating online advocacy with offline efforts can help bridge the digital divide.

FAQs

What steps can online activists take to safeguard their personal data?

Online activists can take steps to protect their personal data and maintain privacy. Start by creating strong, unique passwords for each account and enabling two-factor authentication whenever it's offered. Avoid exposing sensitive details publicly, and use privacy-focused tools like VPNs and encrypted messaging apps to safeguard your communications.

It’s also important to stay updated on data privacy laws and the policies of the platforms you use. Understanding how your information is collected and managed allows you to make more informed decisions. Regularly check and adjust your privacy settings on social media and other platforms to reduce unnecessary data exposure. These simple measures can significantly reduce risks and help keep your personal data out of the wrong hands.

How can we minimise algorithmic bias in online activism?

Minimising bias in algorithms used for online activism calls for a deliberate and well-rounded strategy. A few key actions include relying on data that reflects a wide variety of perspectives, designing algorithms with fairness as a core principle, and performing routine checks to uncover and address any biases that may arise.

Involving a broad spectrum of voices during the development process and openly sharing information about how algorithms function can go a long way in fostering trust and accountability. These steps not only make activism more equitable but also ensure it better connects with and represents the varied needs of different communities.

How can online activism be made more inclusive for marginalised communities?

To ensure online activism reaches everyone, we need to address the digital divide - a barrier that keeps many marginalised communities from accessing technology and engaging in online discussions. This means improving access to reliable digital infrastructure and offering training to boost digital skills, especially in areas that often get overlooked.

Equally important is the creation of safe and inclusive online spaces where marginalised voices are not just heard but actively encouraged. These platforms should welcome a variety of perspectives, steering clear of becoming narrow echo chambers. Building trust through genuine interactions and valuing offline connections alongside online efforts can also play a crucial role in making activism more inclusive. Tackling these issues can help ensure online activism empowers a broader range of communities.